On a summer’s day, walking together in the park, I asked one of my clients the question: ‘how are you finding life at the moment?’ She stopped, mid-walk, turned to me and said: ‘You can’t call this a life.’

I wish I could tell you that there was something unique about what this person told me that day. I want to tell you things that will hearten and uplift you, things that seem fitting for this time of year, good will and all.

But instead I must tell you that this person’s statement about living something less than a life is not unique. During the course of this year we have sat with clients who have told us things like: ‘every day here I am dying.’ We have witnessed their strength diminishing, watching on – sometimes helplessly - as curtains are drawn and people take to their beds. We have seen the women and men we support breakdown in distress, bearing a toll that is actually unbearable.

It is tempting, perhaps, to assume that the responsibility for a decline in the mental health of the people we support lies with the global pandemic. It is true that Covid-19 resulted in many of our clients’ asylum cases being put on hold as solicitors were furloughed and paperwork became harder, impossible even, to obtain. It is also true that the first national lockdown, and subsequent regional restrictions, left many of the people we work with feeling isolated and frightened.

It is truer, however, that the UK’s hostile environment towards people seeking sanctuary in this country is responsible for the acute and chronic deterioration that we are seeing in their mental health. Asylum paperwork is still near-impossible to obtain from the Home Office. Our clients endure repeated assertions that dismiss their identity, nationality, personhood, being, as well as the threat of being evicted, the threat of being detained, the threat of being deported.

‘I’ve been here for thirteen good years,’ one woman tells me who spends her days volunteering, sometimes helping disabled British citizens who have had their personal independence payments (PIP) revoked by the government. That’s a third of her life, I find myself thinking. She contributes so much, gives so much of herself in service to others, and still is forced to live betwixt and between a life and country she cannot return to, and a country that will not accept her.

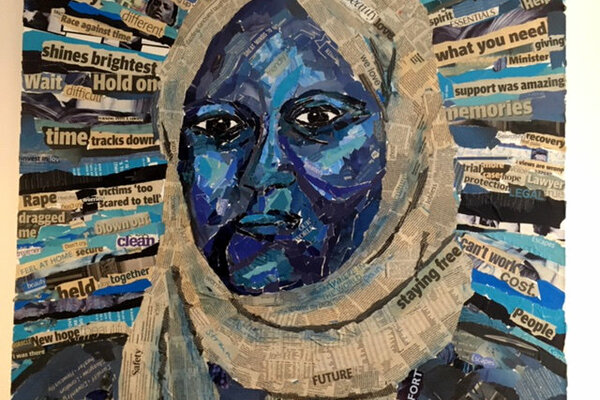

It is in this context, this liminality, that the individuals we support survive. It is in this context that we work, always now with one eye on a person’s mental health and one eye on the headlines.

There are things, our clients tell us, that make a difference: the phone calls and doorstop visits, the walks in the park, the yoga sessions, the sense that one is not forgotten. We are proud that we can do this. But we are conscious that without a sense of safety and security that positive immigration status would afford individuals, it is difficult to actualize a life.

There has never been a time when we have needed your support more than we need it now. Please help us to continue providing the kind of one-to-one support that means we can be alert, and respond, to people’s mental health needs. Please help us to campaign and call for an end to an asylum system that diminishes what it means to be human. Please hold the individuals we support in your hearts and pray for justice to roll like a river.